Hangar 10 (also released as The Rendlesham UFO Incident) is a science fiction/horror found footage film from writer/director Daniel Simpson and writer Adam Preston.

Hangar 10 (also released as The Rendlesham UFO Incident) is a science fiction/horror found footage film from writer/director Daniel Simpson and writer Adam Preston.

The film centers around a couple of metal detecting enthusiasts, Sally (Abbie Salt) and Gus (Robert Curtis), who, accompanied by their videographer friend Jake (Danny Shayler), go in search of a trove of Saxon gold in the forests of Suffolk, England. Their search leads them onto land they discover is controlled by the U.S. Air Force. The trio pushes forward, though, until they encounter mysterious, unearthly lights hovering in the sky. When they attempt to leave, they find themselves lost deep in the forest and discover that a very earthly presence is there with them. As the phenomena appear more and more obvious, the group realizes that they have stumbled into a very dangerous secret, and their lives may be in danger if they don’t find a way out.

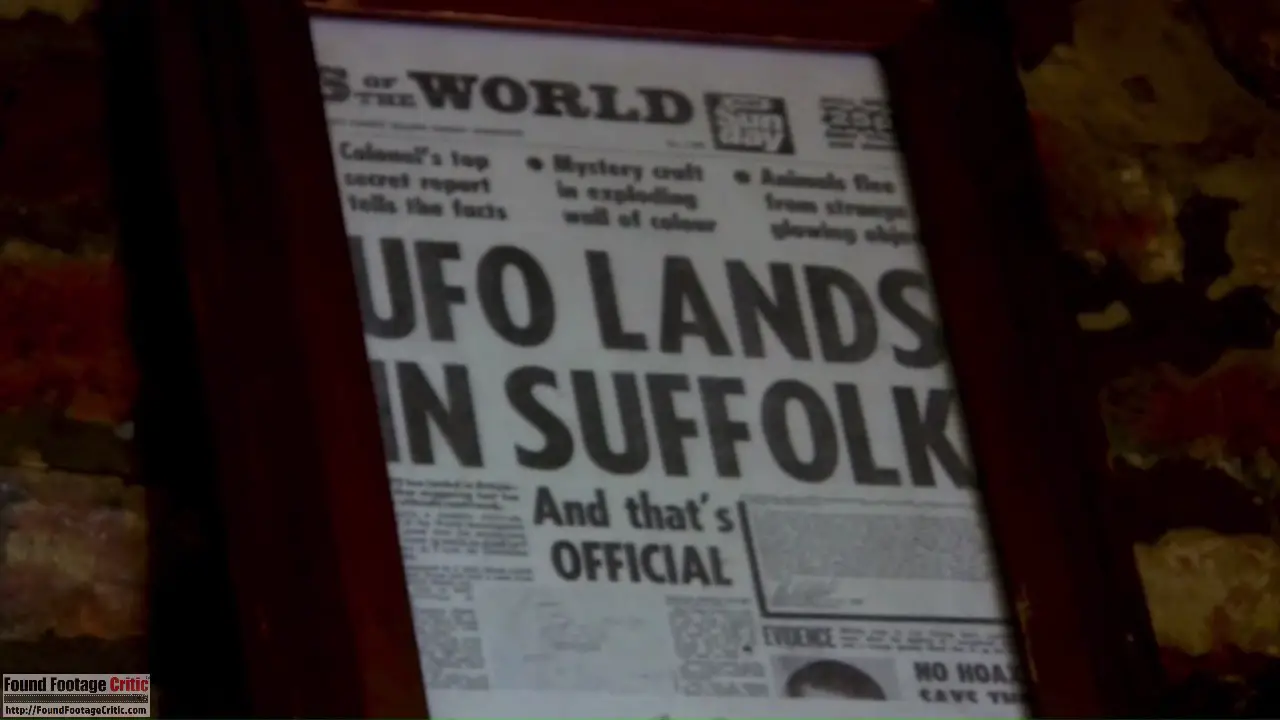

The film is based on an actual series of purported UFO sightings in December 1980 in and near Rendlesham Forest in Suffolk, England, adjacent to RAF Woodbridge, a former Royal Air Force base, being used by the U.S. Air Force at the time. The Rendlesham Forest, from which the film takes its alternate title, has since become one of the most well-known UFO sightings in the world.

Hangar 10 is director Daniel Simpson’s second feature film and his first found footage effort. Simpson also serves as cinematographer and co-writer along with Adam Preston, of whom Hangar 10 is his only feature-length credit.

The given reason for filming begins adequate, but wanes as the movie goes on. Initially, Jake is going along with Sally and Jake to record their treasure-hunting exploits, with hopes of uploading the footage to YouTube. This motive becomes less believable after the group decides to trespass on what they eventually discover is government land, though it’s still plausible he continues recording the events for the group’s own enjoyment. Jake also inordinately films Sally, revealing his lingering feelings for their previous romantic relationship. There is an additional camcorder used primarily by Sally, and the reasons for filming with it are often uncertain, especially in scenes where Jake is already recording with his own camera, and nothing of particular interest is occurring.

When strange things begin to happen, and the group begin to believe that they are in danger, the justification for Jake, and occasionally Sally, to continue filming becomes unclear. In some scenes, the camera’s external light or night vision is used for visibility, but there are long stretches in between where there is no given reason for Jake to be filming as they tramp through the woods bickering. At one point, they witness a particularly dramatic UFO encounter, and Jake and Sally make a point of recording it as evidence. This motivation, however, is not brought up again when they encounter other unusual and potentially dangerous phenomena; unfortunately, as Jake’s determination to prove his UFO theory could have provided a very compelling reason forhim to continue filming during these particularly stressful situations.

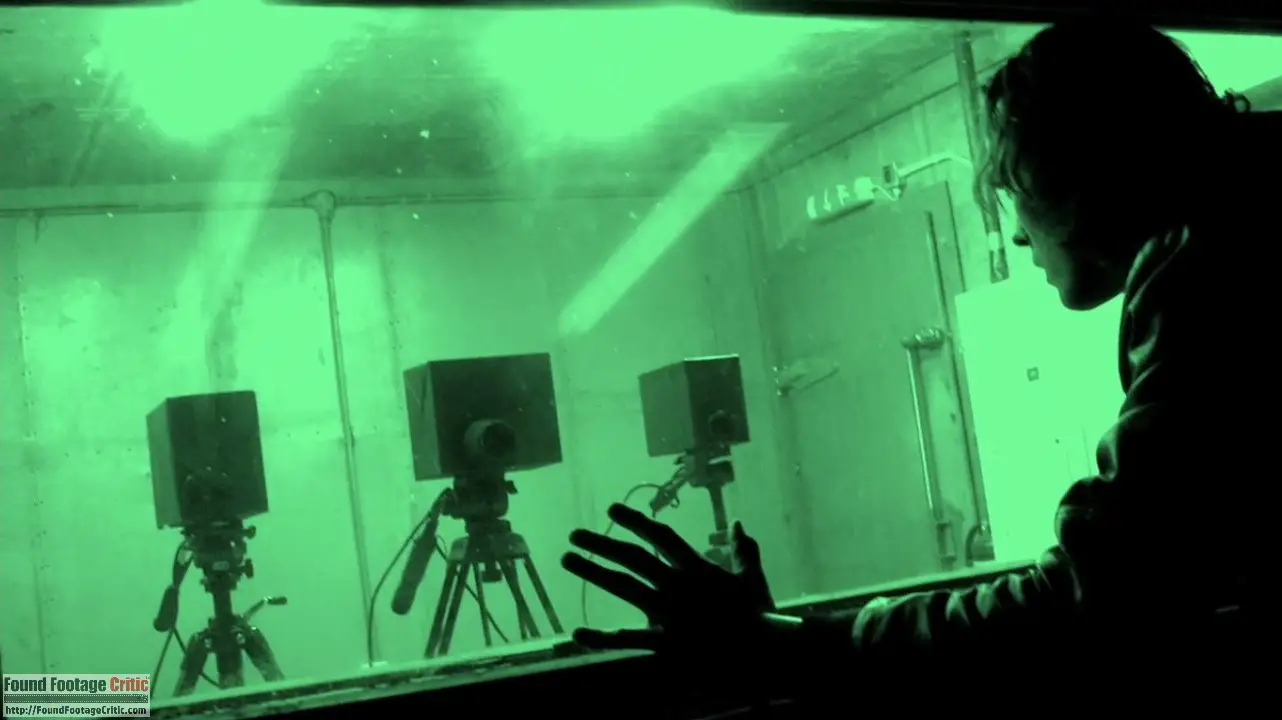

Near the climactic end of the film, two members of the trio find themselves inside a government facility with a seemingly malevolent presence, running around frantically as they try to rescue their friend – some viewers may find themselves screaming at them to just drop their camera(s). Both Jake and Sally carry around their video cameras, though given the urgency of their situation, there is no overly compelling reason provided to continue filming and would very much want to have the use of two arms. This is especially true of Jake who is lugging around a professional-grade movie camera. That one of them would still be filming strains credibility; that both of them would is unbelievable. The only explanation appears to be that they know they are in a found footage film and that if they drop their cameras, the movie will be over.

Found Footage Purity

Much of the first third of the movie does a good job of maintaining found footage purity. Particularly in the first act, the in-camera editing and sound are realistic to the situation. However, as the story progresses, the film on occasion strays from the strictures of the found footage format.

A great strength of the film is its sound design, which succeeds in making the largely unseen threat frightening, with unearthly, haunting noises following our characters. In this way, the filmmakers are able to maintain the presence of the UFOs throughout, while not straining their obviously low, but carefully apportioned, budget. The fact that the sounds are actually occurring in the diegesis (in the world of the story) and are acknowledged by the characters also allows the film to add to its creepy atmosphere, while still obeying the ban on background music necessary to effective found footage.

Yet, later in the movie, the filmmakers appear to become overconfident in their editing. There is one particular out-of-place scene in which Jake telling the group something his father said to him.The scene is edited so that Jake’s dialogue is played over shots in which it is not actually being said. No other scenes contain this sort of editing, and it doesn’t fit with how the framing device presents the footage. The scene, and a few others like it, would be examples of effective and compelling editing in a non-found footage film, but in this context serves to take the audience out of their suspension of disbelief.

Realism/Immersion

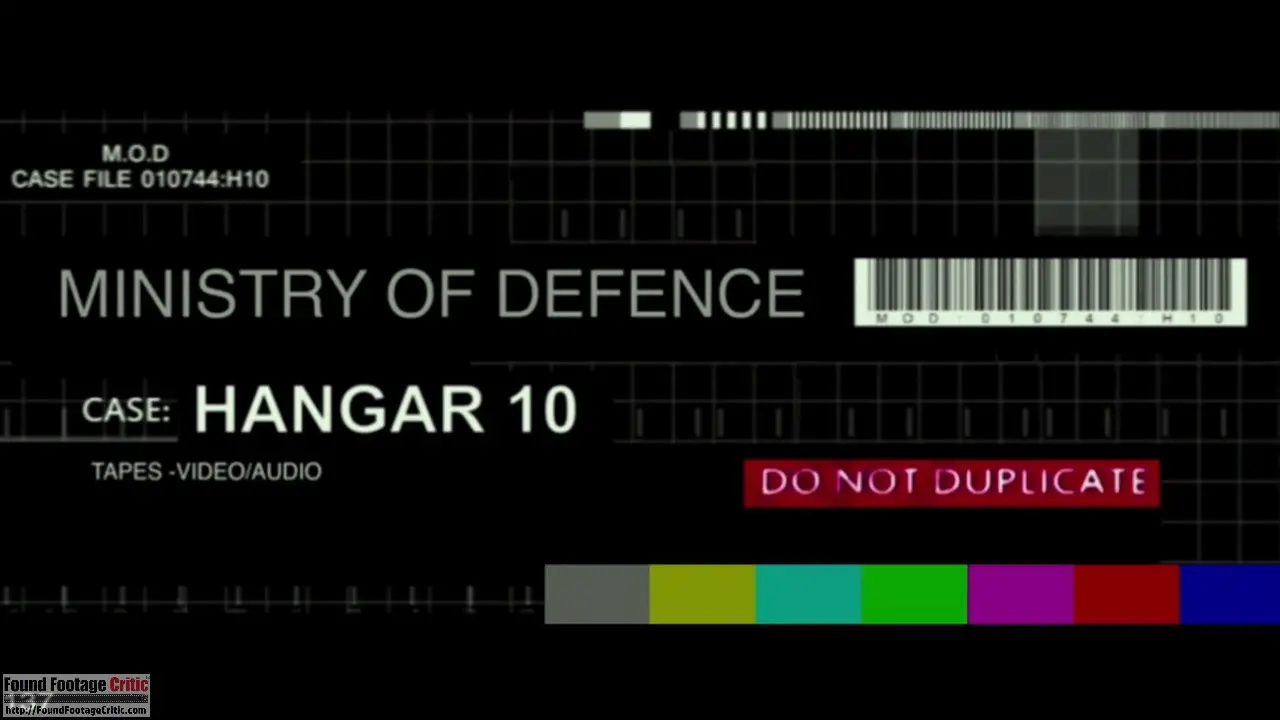

In an interview with Starburst Magazine, director Simpson details his personal interest in the Rendlesham incident, including his belief that reported phenomena were real and are genuine evidence of an alien presence. Obviously, accuracy to the historical events is a high priority of his. The film begins by playing real audio recorded by Air Force Colonel Charles Halt, the most vocal of the alleged witnesses to UFOs at Rendlesham. A title card then conveys that the footage we are about to see was confiscated by the Air Force and only recently leaked to the public. To bolster this supposed fact, the footage is proceeded by a slate declaring the film USAF property and labeling it Hangar 10.

According to Simpson, the movie was filmed over two years in the actual Rendlesham Forest. The scenes which supposedly take place at RAF Woodbridge were in fact filmed at the former USAF base Bentwaters, also located near Rendlesham Here the film diverges noticeably from reality as, while Bentwaters has been abandoned by the military and is now used primarily as a television and film set, Woodbridge has been split into two parts which are actively used by the Army Air Corps and the Royal Engineers, both of whom have been running smoothly since 2006, without any alien intervention. Aside from this, the use of the original locations adds a sense of realism to the film, particularly for believers in the original incident.

Believable Cinematography

For the most part, the found footage cinematography is believable. The camerawork is realistically shaky, particular when the camera is being held by people other than Jake. The film employs an interesting effect, wherein during night vision shots, occasionally the character’s breath can be seen billowing out from behind the camera. It serves as both a reminder of the uncomfortable cold the characters are feeling and adds to the unsettling atmosphere that is pervasive throughout the film.

In general, the cinematography succeeds in bolstering this atmosphere, which imbues the film with tension and a sense of foreboding, even during long stretches in which nothing obviously dangerous or supernatural is happening onscreen. The director creates several excellent, subtly disturbing images, which are enhanced by the bare-bones, unadorned cinematography.

Plot

The plot to Hangar 10 is fairly standard, both for found footage and horror in general: a group of people go out into the woods, get lost, and things quickly go from bad to worse. This simple plot, however, is never dull or overly predictable, as it is carried by the solid acting, creepy atmosphere, and compelling effects.

The film solely follows the three main leads, leaving viewers just as in the dark as they are about everything that happened before they wandered into the forest. Much of the central story is thus left only hinted at or glimpsed in the margins. Virtually everything about the nature of the alien ships, what happened at the Air Force base, and even who has been following the characters since their arrival in is left unexplained. There is somewhat of an explanation of the aliens’ behavior in the last few minutes of the film, but the vast majority of the questions raised are left unanswered. Many films can benefit from leaving some questions open to speculation and interpretation. However, Hangar 10 leaves so many fascinating potential plot threads unresolved, that many viewers will likely find the ending ultimately unsatisfying.

Believable Acting

Hangar 10 stars Robert Curtis (Gus), Abbie Salt (Sally), and Danny Shayler (Jake). As the only actors to appear onscreen, they carry the film largely by themselves. All three succeed at the natural dialogue and emotion that is vital for a convincing found footage film. They are believable as a group of long-time friends; in particular, Curtis and Salt are excellent as a couple. Shayler’s Jake is the most complex character of the three, having had a casual, fleeting relationship with Sally and still carrying a torch. His behavior edges at times into unhealthy and borderline creepy, yet Shayler still manages to make the character likable.

The level of acting is particularly impressive, as none of the actors were operating with a script and the film itself was shot over two years in inhospitable conditions. This is the first feature film role for Curtis and Salt, after a smattering of minor television performances in shows such as Doctor Who and Eastenders. Shayler has limited film experience, though still in minor roles (as well as writing and directing two short films). Despite their relative inexperience and improvising all of their dialogue, the three actors turn in compelling performances.