Frankenstein’s Army is a found footage horror film directed by Richard Raaphorst and written by Chris W. Mitchell and Miguel Tejada-Flores. The film follows an elite squad of Soviet soldiers during World War II. The squad is accompanied by a cameraman supposedly filming their exploits for propaganda purposes. On a mission to to rescue Russian soldiers trapped behind enemy lines, the men find themselves facing off against horrifying creatures made of metal and reanimated flesh. As the rescue mission turns into a fight for survival, the true, darker reasons behind the mission emerge.

Frankenstein’s Army is a found footage horror film directed by Richard Raaphorst and written by Chris W. Mitchell and Miguel Tejada-Flores. The film follows an elite squad of Soviet soldiers during World War II. The squad is accompanied by a cameraman supposedly filming their exploits for propaganda purposes. On a mission to to rescue Russian soldiers trapped behind enemy lines, the men find themselves facing off against horrifying creatures made of metal and reanimated flesh. As the rescue mission turns into a fight for survival, the true, darker reasons behind the mission emerge.

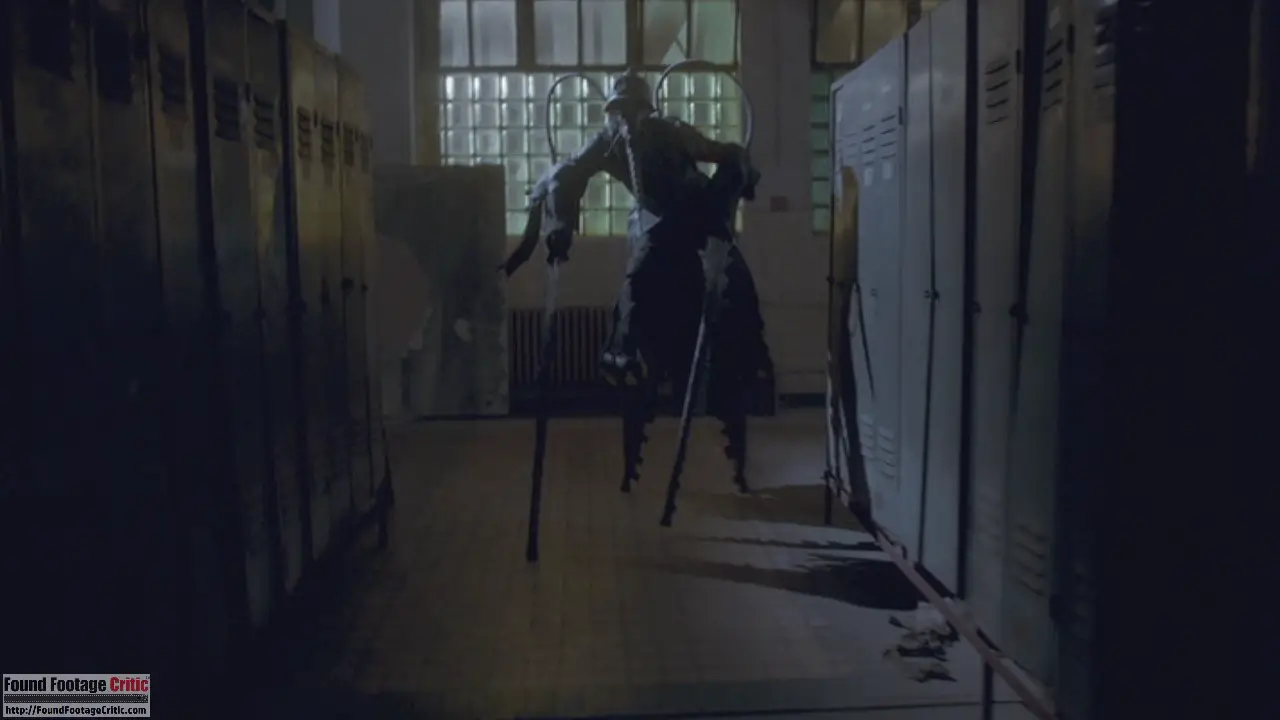

This 2013 Dutch-American-Czech co-production is the first feature-length effort from Dutch director Richard Raaphorst. The majority of Raaphorst’sfilm experience prior to Frankenstein’s Army was as a storyboard and conceptual artist. He fills those roles in Frankenstein’s Army, as well, along with designing the film’s signature monsters. The movie’s greatest strength lies in its practical creature and gore effects. The gore, including a disembowling and a scene of a brain being tugged out of a skull with a helmet, are brutally graphic and well-realized. The design of the monsters – which the credits cutely name Zombots – is creative and by turns frightening and darkly ridiculous.

Reason for Filming

The videographer character Dmitri (Alexander Mercury) has been ordered by the Soviet government to film the mission into German territory. Later in the film, we learn that his family is being threatened if he doesn’t return with the requested footage. During the final ten minutes of Frankenstein’s Army, the filming reason shifts, as he is taken captive and forced by another character to film under threat of violence. Dimitri’s sense of duty and fear of repercussions are set up well enough to justify why he doesn’t just drop the camera when danger strikes, especially taking into consideration the heroic work of real-world war photographers and cameramen.

Found Footage Purity

Frankenstein’s Army compromises its found footage purity quite early with a jarring opening credits sequence. Featuring non-diegetic music and actors’ names placed over footage of them as their characters, the sequence would be interesting and visually-engaging in a non-found footage film. However, in this context they are out-of-place and distracting.

To its credit, the film does manage to stick fairly close to the found footage format for most of its runtime. Toward the end of the film, as Dimitri is wandering through Doctor Frankenstein’s laboratory, there are brief snatches of non-diegetic music: a few notes played on an unseen piano and a tension sting to underscore a frightening moment. On top of undermining the film’s found footage purity, the change in sound design is unnecessary given the strength of the creepy visuals in the scene.

The last few seconds of the film completely break with the found footage format to give information on what happens after filming ends. Again, this moment—although it would have worked perfectly well in a non-found footage film—is jarring as well as superfluous given what we hear the characters saying within the main narrative.

Realism/Immersion

From its outset, Frankenstein’s Army is faced with the problem that handheld camera technology of the 1940s was light years behind that of today. Most cameras of this type only shot in black and white, held very little film, and didn’t record sound. Footage realistic to the period simply wouldn’t be up to modern standards. Color film did exist, some of it of surprisingly high quality, as displayed in the documentary World War II in HD. Even that footage though, is not of the quality of what’s shown in Frankenstein’s Army.

The film does try its best to work around this limitation. At one point in the film, a German being interrogated comments that he’s never seen a camera like the one Dmitri is carrying, including pointing out the attached microphone. We’re led to assume that our characters are filming with some kind of Soviet super-camera. Given how much importance the Soviet military is said to be placing in this mission, it’s not completely unbelievable that they would send the best possible equipment. This justification does raise the question of why the Soviets never went on to use this technology, but this is a minor quibble. The quality of film is a mark against the movie’s realism, but one necessary to the basic premise of the film, and so can be somewhat excused.

Another inherent problem facing the film is that the main characters are Russians, who would logically be speaking Russian. Yet, the film is intended for an English-speaking audience. As their only other option would be to have the actors speak Russian subtitled in English, the filmmakers instead opted to have them speak English with Russian accents. In a non-found footage film, this tactic would be acceptable; the audience is able to understand that even though the actors are speaking English, the characters are really speaking Russian, as indicated by the accents. In a found footage movie, however, everything must be presented on the screen as is. What the actors are heard saying is exactly what is being said in-story. The accent trick is likely to take viewers out of the film in a way it wouldn’t in a non-found footage film. This becomes especially confusing when German characters appear speaking English, leaving it uncertain whether they are actually supposed to be speaking German, Russian, or actually English.

Believable Cinematography

In the scenes where the group is attacked by the zombots, the first-person camera suddenly resembles a first-person shooter video game (a deliberate choice according to Raaphorst in interviews). The cameraman character Dimitri almost always maintains hold of the camera, pointed right at the creatures. While the zombots attempt to kill the other members of the squad with their knives or pincers for hands and faces, they only lunge menacingly at the one holding the camera. In addition to being unrealistic, this also serves to undermine the tension, as, by the second or third attack, viewers are likely to be convinced that Dimitri is in no real danger.

Otherwise the camerawork does appear consistent with the circumstances, with several intentionally poorly framed or tilted shots. In addition, there are a few scenes in which the camera is briefly dropped, lending some realism. The hardiness of the camera after being attacked and tossed around also slightly presses belief.

Plot

The plot of Frankenstein’s Army is relatively simple, but not dull or played out. There are some effective twists and enough bizarre moments to maintain the interest of most viewers. Particularly, there is one reveal at the 40 minute mark that throws the plot and the audience’s understanding of one of the main characters into an entirely new direction. The combination of war, zombie, mad scientist, and found footage movie tropes makes for a fascinating final product, even though none of elements themselves are particularly new. The film does, however, suffer from some inconsistencies in tone, seemingly uncertain of whether it wants to be more gritty and realistic or off-the-wall and ridiculous.

Believable Acting

The film would have benefited from further exploring its characters. The central squad consists of the grizzled leader Novikov (Robert Gwilym), Jewish cameraman Dimitri (Alexander Mercury), young and inexperienced Sascha (Luke Newberry), and level-headed Polish refugee Sergei (Joshua Sasse), vicious and power-hungry Vassili (Andrei Zayats), rounded out with Ivan (Hon Ping Tang) and Alexei (Mark Stevenson). As is, they fit into typical war movie stereotypes. The antisemitism faced by Dimitri, the questioning of Sergei’s loyalty as a non-Russian, and the squad’s simultaneous annoyance at and protectiveness towards Sasha are elements only briefly touched on that could have been fleshed out, particularly given the movie’s relatively short run time. The character with the most in-depth background and motivation is Dr. Frankenstein (Karl Roden) himself, and even then the most interesting detail of his backstory is only described in the end credits.

There is a definite novelty in the premise of a found footage film set in the 1940s. There have been some period found footage films such as 84 Charlie MoPic (1989), Manson Family Movies (1984), and Paranormal Activity 3 (2011), but none of these ventured further back than the late ’60s and early ’70s. The filmmakers should be commended for their creativity in setting, even if they don’t necessarily carry it off realistically (as outlined above).