“Inner Demons” is a found footage horror movie written by Glenn Gers and directed by Seth Grossman. The film follows the crew of an Intervention-style reality TV show shooting a story on a teenage heroine addict, only to find that their primary subject may be fighting more than a drug addiction.

Director Seth Grossman previously directed the drama The Elephant King (2006), sci-fi thriller Butterfly Effect 3: Revelations (2009), and comedy $50K and a Call Girl: A Love Story (2014). His experience also includes producing three episodes of the reality TV show, Intervention (2011), a mere three years before the release of Inner Demons. It isn’t a stretch to suppose that Seth Grossman’s experience on the reality TV addiction show might have informed his direction of the film.

Writer Glenn Gers has a diverse filmography, spanning from the crime drama Fracture (2007) featuring Anthony Hopkins to the Diane Keaton-starring Mad Money (2008) to a Nickelodeon sitcom. Although he had written thrillers prior,Inner Demons is Gers’ first foray into horror movies. Neither Glenn Gers nor Seth Grossman had attempted found footage before.

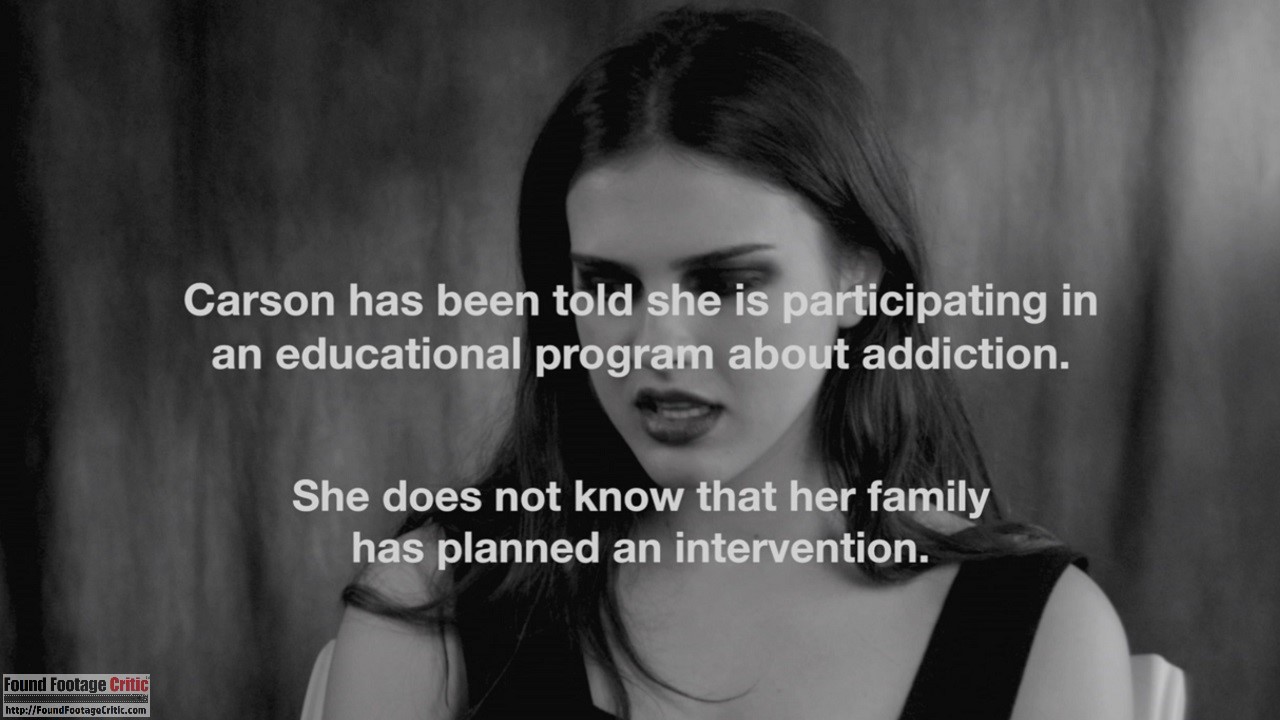

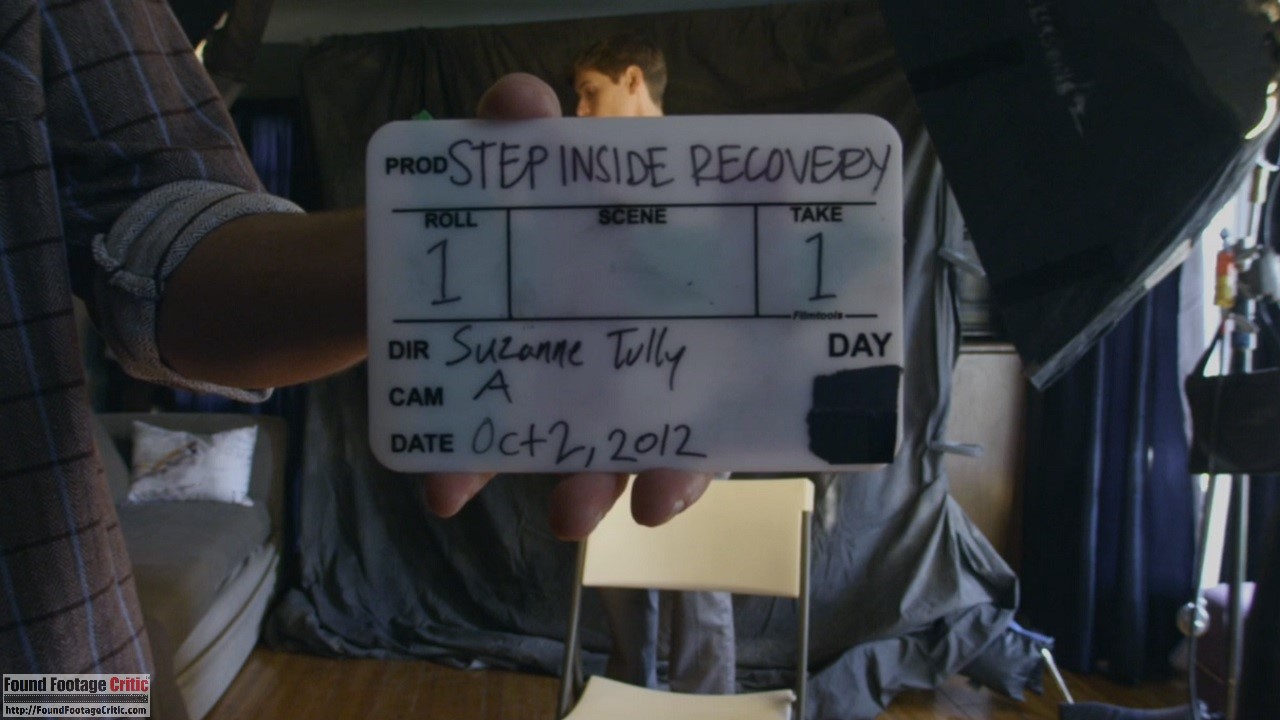

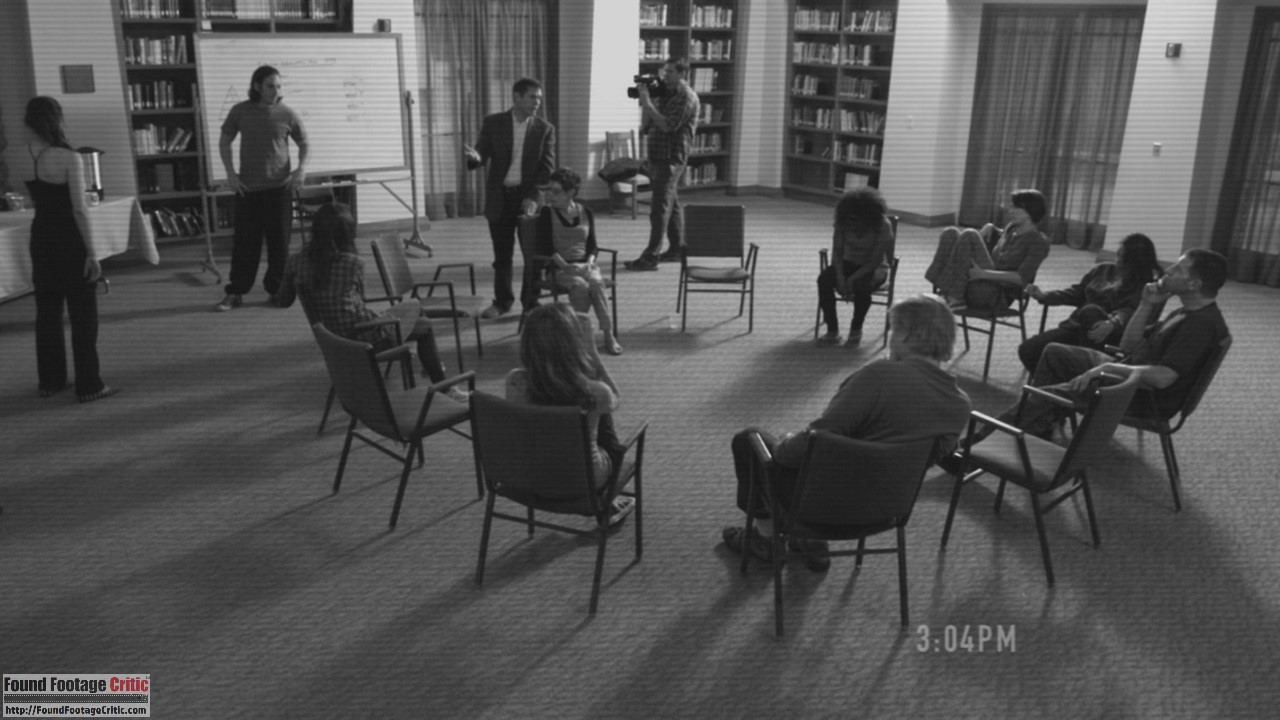

Inner Demons opens with Jason, a young production assistant recently hired by Step Inside Recovery,” an Intervention-style reality TV show. In a similar vein to the real-life TV show Intervention, addicts are filmed being confronted by their families and then followed by cameras going through treatment in a rehabilitation center. The episode Jason is working on focuses on teenage heroin addict Carson. Her middle-class, religious parents describe how her personality abruptly changed when she entered high school, after which she began abusing drugs.

Over the course of filming the emotionally draining episode, Carson reveals that she believes she is possessed by a demon. She tells Jason that she uses drugs to maintain control over the demon. While undergoing detox in the treatment center, Carson exhibits strange and disturbing behavior, leading Jason to believe that she might be telling the truth about her demonic possession. While the rest of the crew is only interested in callously exploiting Carson’s plight, Jason forms a genuine friendship with her and is determined to do whatever it takes to help her, even if it means putting his career and life in peril.

Found Footage Cinematography

The cinematography used in the first two-thirds of Inner Demons fits within the context of a typical Intervention-style reality show. The camerawork in the final third of the film gets progressively (and excessively) shaky, departing from reality TV into the realm of typical found footage movies. Inner Demons uses an array of different camera types, providing an engaging visual variety. Video cameras include two professional-grade handheld video cameras, surveillance cameras, a cell phone camera, and a small tripod mounted camera used for self-confessionals.

The perfect quality of the surveillance cameras is unrealistic, though this is more of a nitpick than anything. Similar to Seth Grossman, cinematographer Chapin Hall has worked on multiple TV documentaries as camera operator, which likely helped him to accurately reproduce the style of the format the film is attempting to mimic.

Filming Reason

The reason for filming in Inner Demons starts out strong, with the characters filming something routine for their job. Later, production assistant Jason makes video notes of himself to document his own search for evidence of Carson’s demonic possession. As with many, even most found, footage movies, the justification for continued filming weakens by the end of the third act as the characters find themselves in immediate mortal peril, in situations in which dropping the video camera would increase their chances of survival.

In the final scene, when the number of justifiable video cameras drops, Carson’s home is suddenly festooned with previously unestablished, high-quality, full-color surveillance cameras. While the number of cameras involved (multiple in the same room even) is excessive, these cameras could have been plausibly explained early in the film. As is, however, the use of these cameras in the climactic scene is out of left field; especially when the action could likely have been sufficiently captured with the one established camera.

Of particular note is footage shot in portrait mode using a cell phone. This scene adds an interesting visual element to the film and highlights a unique aspect of the found footage format. Found footage films intentionally call attention to the source of the visuals onscreen. In contrast, the traditional narrative film aspires to make the viewer forget that there is a camera, the goal being to thrust the viewer into the reality of the film. In found footage, the medium is very explicitly the message. Artifacts of filming—a skewed perspective from filming in portrait mode, a reflection of a camera operator, something bumping into the camera’s mic—enhance realism, rather than distracting from it.

Found Footage Purity

Inner Demons opens with a title card stating that what is to follow is a “rough cut and raw footage” and is “not intended for broadcast.” This introduction effectively hints at the action to follow, offering context for the origin of the footage, while also not divulging too much information.

A sizable portion of the editing and post-production elements included in Inner Demons would be justified in the context of a reality TV show. However, the film fails to explain why heavy editing was applied to a television episode which was never completed and explicitly not meant to air, consisting partly of “raw footage.”

The excessive use of non-diegetic music and slick editing works against the immediacy of the found footage premise. Even if Inner Demons were intended for broadcast, the exaggerated background music added for dramatic effect, particularly in the final third of the film, goes against the grain of even the most self-indulgent reality TV show.

Contrast Inner Demons with films like The Cannibal in the Jungle (2015) or Lake Mungo (2008): both of these horror movies are presented as completed and officially released documentaries. However, with the sanctioned documentary approach claimed by these two films, Cannibal in the Jungle (2015) or Lake Mungo (2008) do not come close to the crescendo of music applied to the final act of Inner Demons.

In particular, the non-diegetic music and sound design undermine the purity of the found footage premise. The use of mood music and orchestra strings to accompany jump scares are tropes common to traditionally-shot horror movies but are wholly out of place in found footage, where the action on screen is understood to largely “speak” for itself. Rather than enhancing the scares, these touches are overall to Inner Demon’s detriment. (Speaking of jump scares, the film overindulges in these to a distracting degree).

Acting

Morgan McClellan (Jason) does very well in the role of the kind, pure-hearted naïf thrown into extreme circumstances. His character’s abrupt transition from skeptic to full believer somewhat hampers Morgan McClellan’s ability to subtly explore that aspect of his character’s development. In the moments which give him room to show uncertainty and self-doubt, Morgan McClellan conveys the depth of his character’s confusion and vulnerability.

Lara Vosburgh (Carson) in effect plays two roles: the drug-addicted teenager and monstrous demon, alternating between dead-eyed and furious. She does well in both parts. Vosburgh’s only previous role was in the Israeli supernatural drama TV series Split (2009), or Khatzuya in Hebrew, though according to her IMDb biography she is active in theater. The other actors do well enough with the relatively thin development they are given.

Plot

At first blush, it appears as though Inner Demon will center on the question of whether Carson’s possession is real or merely a manifestation of her mental illness, playing on the inherent doubt and ambiguity of trying to determine the internal life of a drug-addicted mentally ill young woman. In practice, the movie makes clear quite early on that the supernatural is literally at play. While this tactic does make for a brisker pace, the more complex, nuanced approach would have been more unique and likely more psychologically engaging.

As a consequence of the early introduction of the supernatural, Jason’s arc from open-minded skeptical to the whole-hearted believer is necessarily rushed. As the protagonist, Jason must be more or less at the same level of awareness as the audience. At the same time, the remaining characters appear to be in denial for not noticing or at least adequately investigating Carson’s strange behavior. As an aside, Inner Demon’s entire plot hinges on characters inexplicably never checking the security cameras which record numerous explicitly supernatural events.

Jason makes for a likable, relatable protagonist. He is sweet, naïve, and the only person in the film to show true kindness and understanding to Carson. Carson’s character only comes through in snatches from behind the facade of dazed drug addict or malevolent demon. However, the film intriguingly reveals hints of the tortured young woman beneath. The relationship between Jason and Carson—a friendship tinged with romantic potential—is charming and is likely to increase audience investment in both characters, though some viewers might feel uncomfortable by the age difference (Jason is college-aged, while Carson is a teenager, probably eighteen based on the context).

Jason’s colleagues in the film crew are callous lowlifes, seeing Carson and her family only as a means to an end and source of entertainment, rather than human beings in distress. One sincerely hopes that this is not an aspect of reality TV production that director Grossman gathered from his personal experience in the industry. Even the head doctor at the rehabilitation center mocks his patients’ delusions on camera.

Inner Demons draws upon many tropes pervasive in the horror movies possession subgenre. The demon taunting people about their dead loved ones, speaking in an electronically distorted voice. In one scene a character shouts prayers at a demon-possessed girl writhing on a bed, while the house shakes and an unearthly violent wind blows from some unknown source. While some of these plot elements are a product of horror movies drawing on a common body of lore, others are an obvious reliance on clichés.