“Living Among Us” is an American found footage film written and directed by Brian A. Metcalf. The film revolves around a three-person documentary film crew chronicling the day-to-day lives of a vampiric family living in suburban America after vampires have, proverbially speaking, come out of the coffin and admitted their existence to the public.

The movie begins with a pastiche of cable news talking heads discussing the emergence of a raging vampire disease. William Sadler’s character Samuel is then introduced as the “sectional leader” of these vampires, and he rebuffs accusations that his breed are using blood donation centers to prey upon innocent victims. From there we’re introduced to the three-person documentary film crew – veteran filmmaker Mike (Thomas Ian Nichols), audio ace Carrie (Jordan Hinson), and rookie camera jockey Benny (Hunter Gomez) – who have been invited to spend a few days with a vampiric clan, headed by characters played by Esme Bianco (Elleanor) and John Heard (Andrew).

The film crew soon meets the rest of the brood – the hyperactive Blake (Andrew Keegan), the withdrawn and aggressive Selvin (Chad Todhunter), and twin sisters Sybil and Journey (Jessica Morris and Anna Sophia Berglund.) Despite some kooky occurrences early on, it’s not until the documentary crew witnesses a gruesome ritual that they realize their own safety could be in jeopardy – and soon, they go from being objective observers to the hunted themselves.

Social Satire or Straight Horror?

Social Satire or Straight Horror?

Writer, director and producer Brian A. Metcalf no doubt has a flair for the visual. Before testing the waters as a filmmaker, he worked as a creative director, photographer and visual effects artist on several productions, including a music video for the post-grunge act Helmet and a DVD board game based on the Fox series 24 (2001-2010). This is his second theatrical feature film, following the psychological thriller The Lost Tree (2016).

The found footage medium certainly gives the South Korean auteur a nice canvas for visual-driven storytelling. While the film at first glance appears to be leaning towards a political parody (with the vampires representing the cultural boogeymen du jour), it doesn’t take long for the film to bear its figurative fangs and accelerate into pure horror territory.

That’s not to say there isn’t some humor sprinkled throughout the film, but by and large it’s all played seriously. That entails some pretty icky gore effects later on, so squeamish viewers ought to proceed with caution from the 40 minute mark onward.

Found Footage Cinematography

Living Among Us is a rare found footage film that takes the time to explicitly tell the audience what kind of hardware the characters are working with. An early dialogue exchange lets the viewers know that the footage comes from two DSLR cameras, two handheld cams, three wireless IP cameras, one HD micro cam, and even an old school Hi8 with a “night vision” feature. Additional scenes depict the film through static TV screens (where the bulk of the “vampire outbreak” news reports come in) and even a few iPad conversations.

While Living Among Us employs all of the camera setups to achieve its found footage effect, a large portion of the film is depicted through the P.O.V. of Benny’s professional grade camera. Considering the movie primarily takes place in one house, Metcalf impressively manages to find shots and angles that keep the backgrounds and foregrounds from repeating, and even some of the stationary shots (be forewarned, the “dinner” sequences in the film drag on for some time) are still pretty interesting. Give Metcalf and co-cinematographer Evan Okada some credit, these guys have an uncanny knack for making onscreen food look positively horrifying.

The only major cinematographic miscue in Living Among Us are the nighttime scenes. The pseudo-night vision effect doesn’t work very well, and a lot of times you’ll strain your eyes to interpret what’s supposed to be going on in the shot. But as a positive, those scenes are few and far between.

Alas, the film loses some realism points for its audio. There are several sequences where characters – far away from any camera and certainly not mic’d up – sound as if they are right next to the equipment. This is most notable in a scene where the camera crew spies on two vampires making out in a swimming pool – even though the crew is recording the tryst from 20 feet above, their equipment picks up every swish and squish below as if they had a camera floating in the water.

Despite the few challenges discussed above, Living Among Us does a commendable job at simulating what could conceivably be recovered found footage.

Filming Reason

Since the entire premise of the film revolves around a documentary crew’s project, the hook makes perfect sense. Taking a page from the old Blair Witch Project (1999) and Ghostwatch (1992) playbook, the most enjoyable part of the movie is watching the disbelieving crew slowly but surely realize just how bad of a situation they’ve gotten themselves into, all the while doing the best they can to not abort their documentarian mission.

I suppose casual filmgoers may have some difficulties suspending their disbelief at certain moments in the movie. But just ask anybody who’s ever been on a real documentary film crew before – they’re more than willing to risk life and limb just to get the shots they really want in the final cut.

The non-first person footage – i.e., the cable news pastiches, the iPad chats, etc. – serve a purpose in advancing the plot, but they don’t come off as particularly striking visuals. Overall, though, Living Among Us adheres to the basic ground rules of the modern-day found footage horror film rather well. And considering the film is clearly meant to be a horror-comedy hybrid, we can cut the filmmakers some slack—after all, the movie is by design meant to feel a bit campy.

Found Footage Purity

In terms of general presentation, Living Among Us looks quite good for its budget, but as a traditional found footage flick it’s not always convincing. This is one of those found footage flicks that falls into a mostly unhappy medium. For the most part, it’s just too glossy and well-lit to realistically replicate the footage it depicts, but when it does break out the less high-tech camera work, the end results are perhaps a bit too dark and grainy, especially those almost indecipherable nighttime outdoor sequences.

The biggest problem with the film is easily the special effects. The practical gore makeup is quite good (although there is some clunkiness in the movie’s first major bloodletting scene) but the computer-generated effects are challenging throughout.

Another unfortunate aspect of the presentation is the inclusion of CGI static screens to represent jump cuts, which have no real technical reason for showing up. Since the rest of the footage is so polished, these cuts look like they were edited by a third party, and are likely to take viewers out of the experience.

There’s one other element of the movie that is likely to distract viewers; the inclusion of well-known actors may take away from the found footage conceit. While we can’t knock a film for using known actors, it certainly would have been more absorbing if you weren’t thinking aloud: “Hey, that’s the dad from Home Alone (1990)!” every five minutes.

Given that Living Among Us is a faux documentary with an intentionally campy air to it, and in the same vein as the similarly themed What We Do in the Shadows (2014), the found footage conceit stands up well for what is presented.

Acting

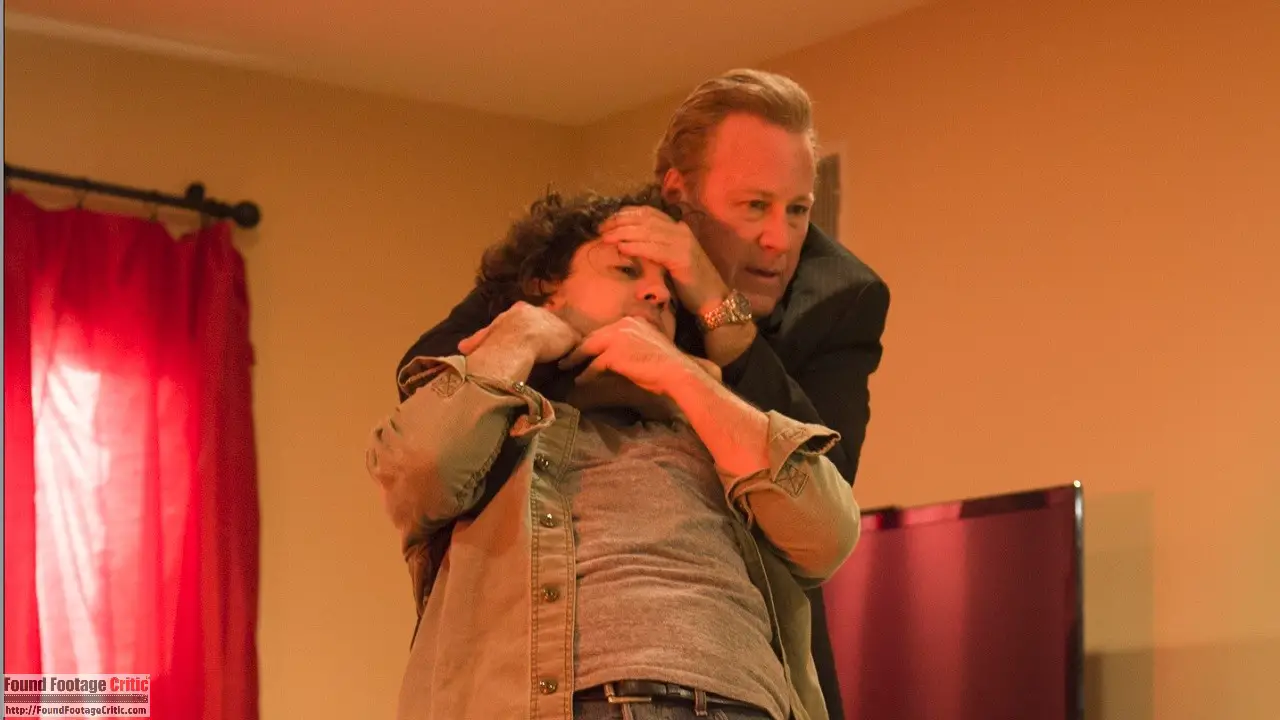

The acting in Living Among Us is a mixed bag. Most of the performances are good, but not great. The cable news anchors come off as wooden and a little clunky. And even veteran actors like the late great John Heard (in his final role as Andrew) and William Sadler (as Samuel) have a tendency to dip into overacting at times.

The ensemble cast is something of a potpourri of your usual subgenre stock characters. Benny is your standard, overly excitable first-time crewmember, Mike (Thomas Ian Nichols) is your painfully hip and with it tech wizard and Carrie (Jordan Hinson) is pretty much there to play a buffer between the two clashing male egos. Andrew and Eleanor (Esme Bianco) are fairly interesting antagonists, although they never really have any opportunities to show much pathos and character development. The rest of their brood is a bit one-dimensional, although the kinetic disposition created by Andrew Keegan’s character Blake is a fairly decent foil for the rest of the vampiric clan.

Circling back, do fall on the somewhat hammy side. William Sadler appears to be phoning in his performance as a “via satellite” vampire dispelling myths about bloodsuckers, while the litany of faux news anchors look visibly anxious and struggle to deliver their dialog. As discussed earlier, the general approach to the acting and character development falls squarely within the sometimes comedic and lighthearted/campy nature of the film.

Plot

There’s nothing exceptionally inventive about Living Among Us, storywise. We’ve no doubt seen this formula before in other horror movies – What We Do in the Shadows (2014) being a stellar example. In fact, there are many parallels between those two movies, despite Shadows being more of a tongue-in-cheek comedy. Naturally, one has to wonder how much the director of Living Among Us was influenced by the 2014 Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement mockumentary; regardless.

On the downside, there are scenes that drag on for longer than they should, and the sometimes challenged acting is likely to take the viewer out of the experience at times. Nonetheless, the film is entertaining for what it is.

The strength of Living Among Us is its practical effects. Without giving away any key plot points, let’s just say that when the red stuff starts splashing, it gets spilled by the bucket. There’s a certain unpleasantness to the violence as well, which is a welcome change of pace from the inconsequential mayhem of many of the film’s contemporaries. All things considered, you have a final product that, despite its shortcomings may be worth a look for vampire fans.