Welcome to the Jungle is a found footage horror film written and directed by Jonathan Hensleigh. The film is a nostalgic callback to the cannibal exploitation subgenre of the 1970s and 1980s, with a modern setting.

Welcome to the Jungle is a found footage horror film written and directed by Jonathan Hensleigh. The film is a nostalgic callback to the cannibal exploitation subgenre of the 1970s and 1980s, with a modern setting.

Welcome to the Jungle follows in the footsteps of Cannibal Holocaust (1980), as well as the larger cannibal exploitation subgenre the film is a part of—including movies such as Cannibal Ferox (1981) and the recent throwback, The Green Inferno (2013). However, Welcome to the Jungle sets itself apart by basing its plot on the true story of the disappearance of Michael Rockefeller. Rockefeller, heir to the American millionaire dynasty, disappeared in 1961 while on a scientific expedition in New Guinea. The boat containing Rockefeller, two native guides, and a Dutch anthropologist overturned. After the two guides attempted to swim for help and failed to return, Rockefeller followed them. The Dutch anthropologist was later rescued, but Rockefeller was never found. After a massive manhunt funded by his wealthy politician father, Rockefeller was declared dead three years later. The truly fascinating story is covered in detail in the documentary The Search for Michael Rockefeller (2011), available on Netflix.

Controversy has swirled around the case since 1961 and continues to this day, with numerous claimed sightings over the decades. In all likelihood, Rockefeller drowned while attempting to reach the shore. However, some believe, within the realm of possibility, that he was killed and eaten by the cannibalistic Asmat tribe as revenge for an earlier killing by Dutch officials. Others believe that Rockefeller was not killed, but held captive until eventually “going native.” This latter theory was afforded some, admittedly slight, evidence by footage shot years after the disappearance—uncovered and presented by the documentary crew for the first time—which shows what appears to be a white man loosely fitting Rockefeller’s description living amongst the natives.

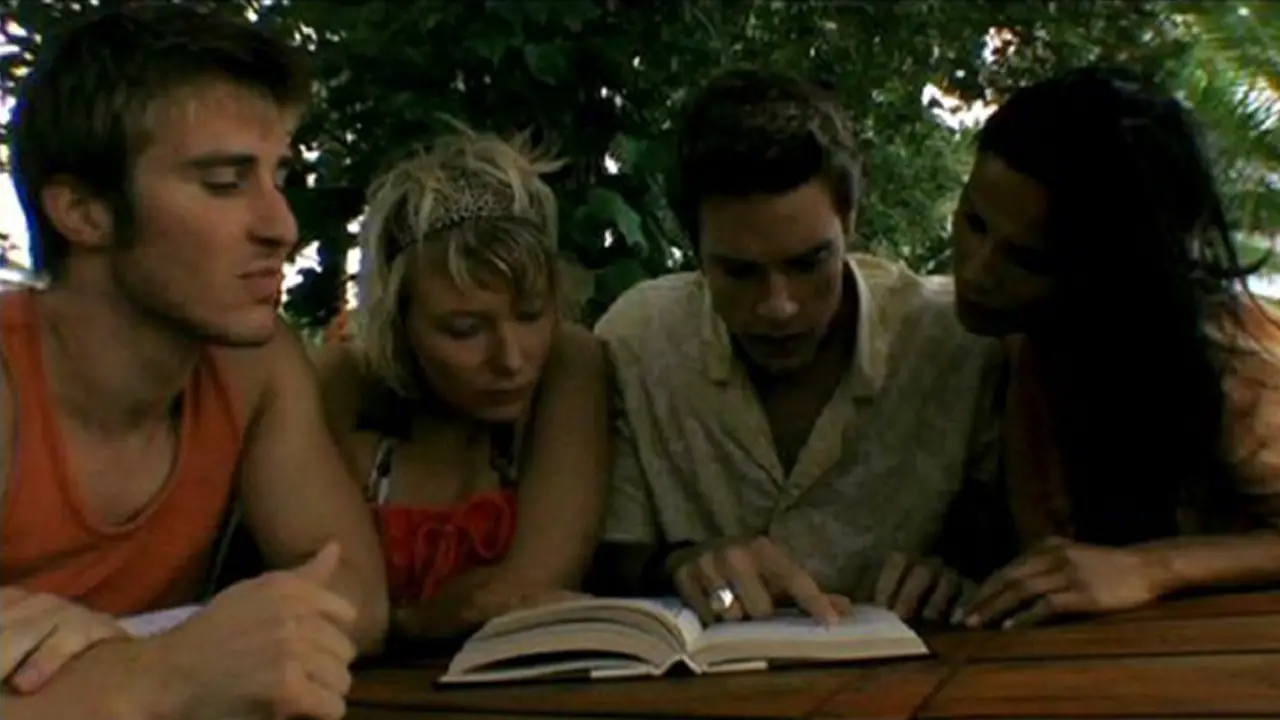

The plot of Welcome to the Jungle begins with Australian expatriate Mandi (Sandi Gardiner), living in Fiji, inviting her friend Bijou (Veronica Sywak) to visit. Bijou resents the presence of Mandi’s American boyfriend Colby (Callard Harris), until he introduces her to his fellow American Mikey (Nick Richey), who she quickly hooks up with. Colby reveals that he heard stories of an elderly white man spotted living with an uncontacted indigenous tribe in the New Guinea jungle, who he thinks might be Michael Rockefeller. Lured by the promise of money, the group decides to journey into the jungle with their video camera to find Rockefeller and hopefully interview him. As they journey deep into the jungle, however, internal divisions between the would-be explorers set in, eventually leading them beyond the point of no return.

Welcome to the Jungle is helmed by writer/director Jonathan Hensleigh, who has achieved Hollywood success writing films including Armageddon (1998), Jumanji (1995), Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), and The Punisher (2004), which he also directed (one of his three directing credits, including Welcome to the Jungle). Welcome to the Jungle is Hensleigh’s first attempt at both horror and found footage. He is also credited as cinematographer on the film. In his director’s commentary (available on the DVD, along with a featurette on the making of the film), Hensleigh says that he was originally asked to write a big-budget remake of the 1954 Charlton Heston film The Naked Jungle, also set in a jungle, but with Heston squaring off against legions of army ants, rather than cannibals. When that project fell through, Hensleigh instead turned his attention to creating a micro-budgeted horror film, inspired by the cannibal boom of the 1970s and 1980s.

Found Footage Filming Reason

The filming reason starts with a group of friends recording their vacation. What they choose to film is, for the most part, believable: meeting up, having fun in a bar, goofing around, and ogling strangers. In a refreshing twist on a tired found footage cliche, the girls film unsuspecting men. After the initial set-up, the filming reason shifts to recording evidence of Michael Rockefeller living in the jungle. What isn’t entirely clear, however, is why the group film every detail of their journey, including their mundane spats and wandering through the jungle, even setting the video camera on the ground to record themselves binge-drinking. They aren’t journalists or scientists and never express an interest in filming a documentary, which might justify recording the journey itself.

This lack of motivation causes even more obvious problems when the characters are placed in danger. There is no reason for them to cling to the video camera while they are running and cowering in fear of their lives. The video camera isn’t even used as a makeshift flashlight, a common justification used by found footage films in similar situations. In the last few most action-packed minutes the nagging question of “why doesn’t she just put down the video camera and run?” is impossible to ignore.

Also of note, the group is the jungle with limited provisions and supplies, including a finite number of batteries. To justify the group’s prolonged filming, one of the characters indicates that they are equipped with a solar powered battery charger. While the battery charger indicates “how it’s possible to film so much, the film doesn’t clear convey the “why.”

Found Footage Purity

For the most part, Welcome to the Jungle does a good job of maintaining found footage purity. There are three notable exceptions, two relatively easy to overlook, the other a frustrating deviation from the expectations of the subgenre.

The film begins with a few short title cards introducing the Michael Rockefeller story. Even presented simply, the inherently unsettling nature of the facts of the Rockefeller case do serve to set the mood—though this preliminary background information is for the most part also covered by the characters within the film itself. Hensleigh makes the odd decision to delineate footage taken by different video cameras with introductory titles reading Camera #1 and Camera #2. This device might be useful in a film comprised of footage from many sources intercut together. In Welcome to the Jungle, however, the film only uses two video cameras, with the footage presented serially with no complex intercutting. The introduction of the second video camera is even done verbally, so no viewer could reasonably be confused as to where the footage was coming from.

All of the added titles indicate that the film is supposed to take the form of raw footage edited into a documentary format, similar to the way in which title card and editing choices were integrated into Paranormal Activity (2007). However, within the body of the film, there is nothing supporting this approach. Most crucially for the edited documentary conceit, there is no indication of how the footage could possibly have ended up in the hands of a documentarian, as is the case with the video cameras left around Micah and Katie’s house.

More distracting and intrusive, though, is a bizarrely over-edited scene in which Mandi, Bijou, Colby, and Mikey discuss their journey into the woods. Bijou and Mandi talk while casually shooting pool, the single video camera resting on the table. In any other found footage film, this scene would have been shown in a single medium shot. Instead, the conversation consists of intercut close-ups on Mandi and Bijou. It is impossible that these could have been captured with a single unmanned video camera—improbable even for two video cameras filming simultaneously. The scene itself is cut together with separate scenes of characters speaking directly into the video camera, with the two sets of dialogue cut together to form one continuous conversation. This editing trick is completely out of place in a found footage movie, challenging the suspension of disbelief. The scene is indicative of the director’s unfamiliarity with the found footage format.

Realism/Immersion

The jungle scenes which make up most of the latter half of the movie are filmed in Fiji. The beautiful and ominous landscape adds an important sense of realism and atmosphere to the film. Viewers are likely to connect with the characters’ isolation and sense of hopelessness as they journey further into the heart of the jungle.

The plot, however, features many unrealistic elements. Firstly, there is the question of how these four random young people, with no apparent expertise in cartography and navigating alone in the jungle, are able, with little effort, to locate Michael Rockefeller where decades of journalists and explorers with fortunes behind them had no success. The plot requires the acceptance of this wholly unrealistic premise, though the characters’ general incompetence and lack of common sense make it difficult. Another major unanswered question is how the main characters are able to take a barely-planned trip into the unexplored depths of the Fijian jungle, loaded with high-grade equipment at the drop of a hat.

The pinnacle of the film are the gore effects. Perhaps the film’s saving grace, the practical effects are realistic and stomach-turning. It’s unfortunate that there weren’t more of these scenes to further showcase the effects. The special effects team, consisting of Gary J. Tunnicliffe, Mitchell J. Coughlin, Jane O’Kane are all seasoned professionals with a panoply of successful films on their resumes. In particular, Tunnicliffe is a 23-year veteran who has worked on at least sixty films, including Candyman (1992) and the Hellraiser (1987) sequels.

One particular poorly executed subplot involves the characters splitting up. Two of the characters opt to build a raft to navigate a very deep and dangerous river. Forgetting about the length of time and skill required to build a raft, both of which these characters fall woefully short of, is the fact that the remaining two characters also decide to build their own raft to chase after the first two characters. The film clearly uses the same raft for both scenes—with the same knots and same exact protruding lengths of bamboo. This lack of detail further challenges the already strained suspension of disbelief.

Cinematography

The cinematography in Welcome to the Jungle is competent and unremarkable for found footage. Aside from the scene discussed earlier, the camerawork isn’t particularly unlikely or overly cinematic. The film contains a few scenes where the video camera is dropped or picked up by unseen figures, adding to the mood and visual interest.

A particular scene that stands out early in the film consists of a composite of shots where the four main characters speak directly into what appears to be an unmanned camera. The shots call to mind the format ubiquitous to reality TV. The scenes would fit smoothly into an episode of Big Brother or Survivor or possibly someone’s vlog. Although plausible within the found footage format, these shots are more distracting in the different genres they evoke.

Plot

Welcome to the Jungle’s writing is the film’s weakest point. The film is slow-paced, and not in a manner that builds atmosphere or tension. Unfortunately, the film is laden with characters chattering and bickering. The story contains spikes of action, such as when the characters are shot at by thieves and later Indonesian soldiers, but these are brief and not developed enough to create a true sense of danger or heightened stakes. It isn’t until the final twenty- minutes or so that the action truly begins.

Welcome to the Jungle is often criticized as a thinly-veiled rip-off of Cannibal Holocaust (1980). In reality, Welcome to the Jungle is no more similar to Cannibal Holocaust (1980) than it is to any other film in the subgenre, other than its found footage set-up. However, comparisons are inevitable between a revival film and the high water point of the genre. What ultimately works against Welcome to the Jungle is how overall tame the plot is in comparison to its outrageous forebearers. Virtually no violence appears until the latter half of the third act.

Beyond the stunted pacing are the characters who are both profoundly unlikeable and uninteresting subjects to follow. Bijou, Mandi, Mikey, and Colby are a group of seemingly wealthy, directionless first-world twentysomethings who go on the central adventure out of a combination of boredom and greed. There is no explanation of why they might need the money—since all are apparently able to blow off their jobs on a lark—which could have added some depth to the characters. Each character is extremely shallow and stereotypical. Colby and Mikey are sex-obsessed frat-guy types. Bijou is an alcoholic party girl. Mandi is a virtual blank slate, allegedly more responsible than Bijou, a trait that fades in and out of prominence depending on the scene. Each of these characters is a sterling example of the “ugly American” (or Australian, as the case may be).

Unsympathetic protagonists aren’t necessarily a flaw, particularly in an exploitation film. The characters in Cannibal Holocaust (1980). are a group of sadistic, amoral rapists and murders, who are ultimately deserving of their grisly fate. However, the documentarians in Cannibal Holocaust (1980) reach a level of evil that becomes sickeningly fascinating to watch. Alan Yates, in spite of his cruelty and selfishness, is a charismatic presence. Viewers are baited to guiltily watch with bated breath to see what atrocity he will commit next. (Even, so, the film also has the parallel story of the relatively likable Professor Monroe, played by the legendary Robert Kerman). The characters in Welcome to the Jungle are, in contrast, simply obnoxious. Their negative traits never rise to the level of compelling evil.

The Michael Rockefeller element of the story is underutilized. Almost none of the details outlined above are even mentioned. The aura of mystery and danger surrounding the original case is absent. The Rockefeller plot itself ends up playing a very small role in the overall story; the goal of searching for Michael Rockefeller could have been replaced with a search for any McGuffin, human or otherwise. Some of the most interesting aspects of the real case, such as the identity of the tribe who may have killed and cannibalized him or their possible motivation for the murder, are left unmentioned, where they could have contributed to a deeper, more disturbing and engaging story.

Acting

The cast is one of relative unknowns, with various roles in small films and television Most seasoned is Callard Harris (Colby), who had recurring roles on The Originals (2013), the 2012 Dallas, and Sons of Anarchy (2008). Also of interest, Sandi Gardiner (Mandi) is the holder of the 2015 Guinness world record for helping to create the most successful crowdfunded project ever, serving as VP of marketing on the upcoming video game Star Citizen.

The actors are unfortunately not given much to work with for most of the film. The characters are overall unlikable, and their motivations left mostly vague. Harris and Gardiner do get the opportunity to turn in quite compelling performances in the last act of the film when the stakes are actually raised.